“The way we see things is affected by what we know or what we believe” (Berger, J. 2008, page 5)

Memes are a prime example of how our interpretation of text and images is affected by our surroundings. As seen in my previous research, memes have become a tool for post-millennials to set themselves apart and create almost a new language. A language dictated by the content we consume.

We need to be able to question why Gen Z feels the need to create their own language. Roberta Katz et al, authors of Gen Z, Explained: The Art of Living in a Digital Age, explains “The experience of Gen Zers is therefore often paradoxical, even contradictory. They have more “voice” than ever before…but they also have a sense of diminished agency “in real life”…They are often optimistic about their own generation but deeply pessimistic about the problems they have inherited: climate change, violence, racial and gender injustice, failures of the political system…” (page 11, 2021). It seems to be a form of coping to use humor in order to adapt to the state of our surroundings. By creating our own social codes, we are maintaining a sense of evolution and growth within certain subcultures on the internet, perhaps as an outcome of not being able to commit purposeful change to the world outside our groups of familiarity.

It is clear that Gen Z have been able to differentiate themselves from other groups online. “Gen Zers articulate the difference between themselves and the members of older generations in terms of their recognition and observation of social codes online. The failure of older users to “get” these intricacies is the source of some postmillennial puzzlement.” (Roberta Katz et al, page 19, 2021). This differentiation comes down to how these groups online were able to create their own inside jokes that vary within the subcultures.

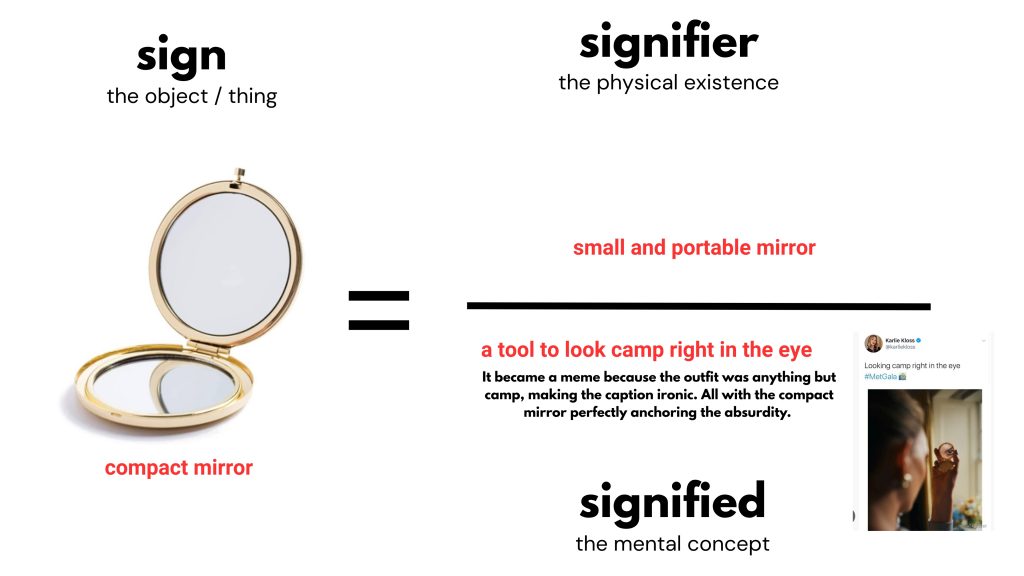

When it comes to memes within the Gen-Z queer adjacent chronically online environment, interpretation plays a big role. We would need to start at the foundation, which is Ferdinand de Saussure, who laid the groundwork for semiotics. Saussure described the way we understand things and meaning as being made up by the signifier and signified (Saussure F et al. 2013). In the context of memes, the signifier would be the image, while the signifier is the meaning behind it. By understanding the signifier, it almost becomes an affirmation of belonging and being in the know. While Saussure’s theory focused on language, it can still be interpreted into all forms of cultural communication, which includes memes.

There are different levels of which a meme can be understood, as meme culture is considered unstable. “Meme culture is characterizable as a heterogeneous mixage of cultural forms and can thus be more precisely designated as a “mash-up” culture, rather than a bricolage one.” (Danesi, M. 2019, page 40) One meme can be an outcome of a series of iterations that came from an initial meme. The influences on the iterative cycle of the meme are also influenced by one’s subculture. For example, the addition of music, a certain editing style, or a quote ends up remixing this meme to be understandable to the nano-subculture of what was originally represented. “In meme culture, intertextuality breaks down— memes may, of course, allude to other memes, but the whole allusive structure is unstable given the ephemeral nature of memes themselves. Of course, if the allusive system taps into a long-standing intertextuality, then the meme may acquire historical substantiation.” (Danesi, M. 2019, page 76).

The process of how a meme comes to life can even affect an everyday object that is included in that meme to become a cultural sign. “An Internet meme can of course become a cultural item, even crossing over into the art world— but it somehow transforms the latter. An example of this is the Grumpy Cat meme— which has migrated from the Internet to other areas of representational culture, including to art museums.” (Danesi, M. 2019, page 46), This ultimately goes back to my topic of offline artefacts.

Gen Z wants “relatable” content in their online communication (Roberta Katz et al, page 27, 2021). They yearn for a sense of belonging through the memes they consume. It is also important to acknowledge that subcultures can be easily created around any issue, topic, aesthetic, etc (Roberta Katz et al, page 96, 2021). Some examples of very specific online subcultures would be:

- Hyperpop Alt Scene

Queer, Digital maximalism, irony-filled, cyber-femininity, referencing PC music artists like SOPHIE, Charli XCX.

- Americana Folk Alt Scene

Can be viewed as the darker side of the hyperpop alt scene, grainy content, low exposure, boho referencing sad girl indie music like Ethel Cain, Phoebe Bridgers.

It is important to acknowledge the cultural semiotics in order to understand the direct tie that is intertwined between the objects, memes and the visual culture around it. Ultimately connecting the offline artefacts to larger systems of meaning.

References:

Berger, J. (2008) Ways of seeing. London : Penguin

Danesi, M. (2019) Memes and the future of pop culture. Boston : Brill

Katz, R. Ogilvie, S. Shaw, J. Woodhead, L. (2021) Gen Z, Explained: The Art of Living in a Digital Age. Chicago : The University of Chicago Press

Saussure F. d., Harris R. and ProQuest (Firm). (2013). Course in general linguistics. London: Bloomsbury