This intervention was designed to explore whether stakeholders can identify everyday offline artefacts. Are people able to decipher everyday items and spaces that have gained meaning through memes as offline artefacts?

To receive the most results possible, I decided to do the intervention as a “quiz” followed by a survey to acquire additional information. To make sure the intervention did not feel like a questionnaire, I made sure that the quiz portion was not data-driven but rather kept open-ended to get unhindered reactions and response. This allowed for more personal interpretation instead of just a “right or wrong” option. Emphasising the way of seeing how people communicate regarding their familiarity and relationships towards the offline artefacts.

I wanted to do an offline approach because I felt participants felt comfortable sharing and referencing memes. Additionally, the anonymity of the intervention has netted more authentic results that would not have been as fruitful if done online. The intervention consists of offline artefacts with the ability for the participants to enter anything they would like. A link, text, nothing, or anything at all.

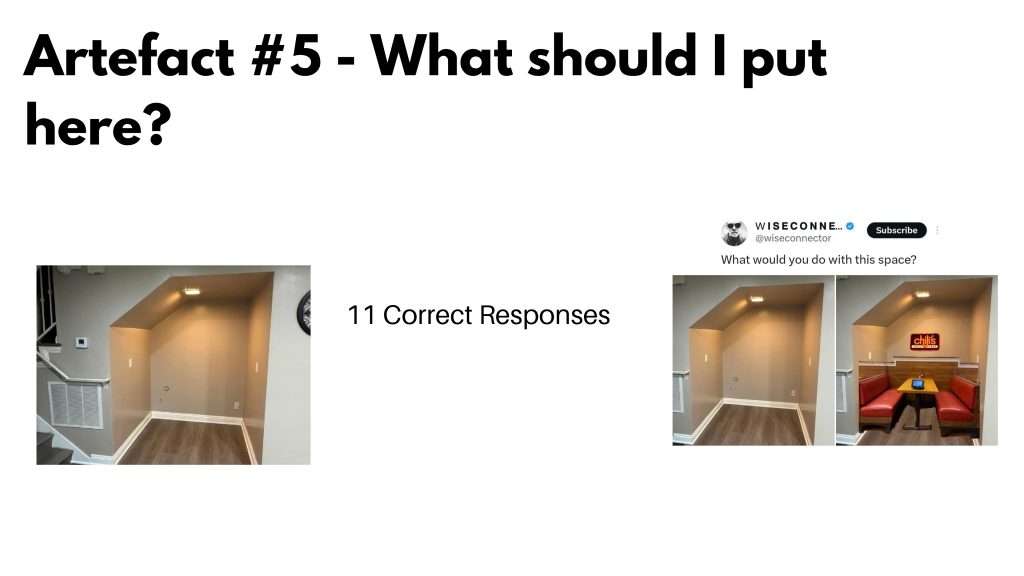

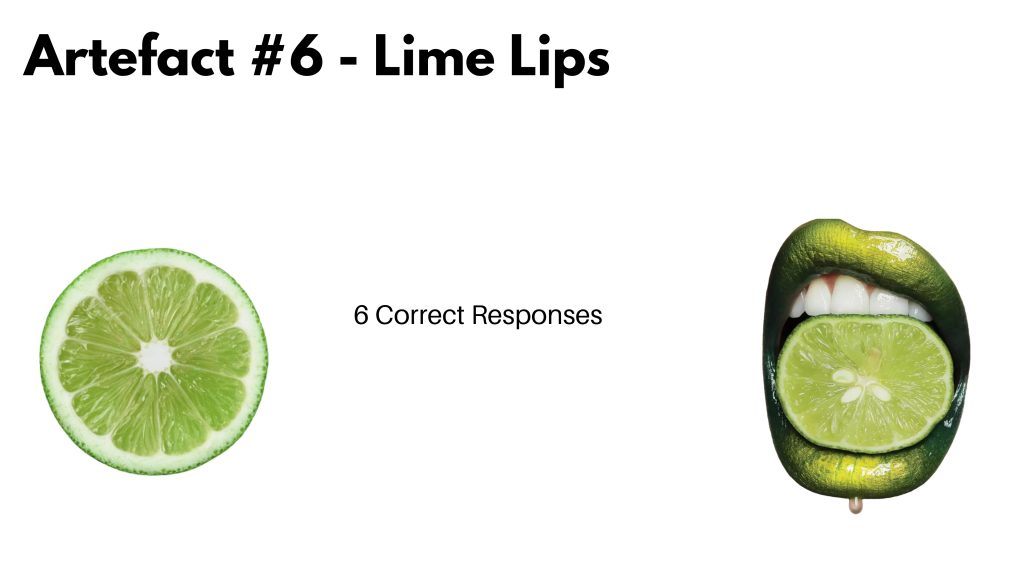

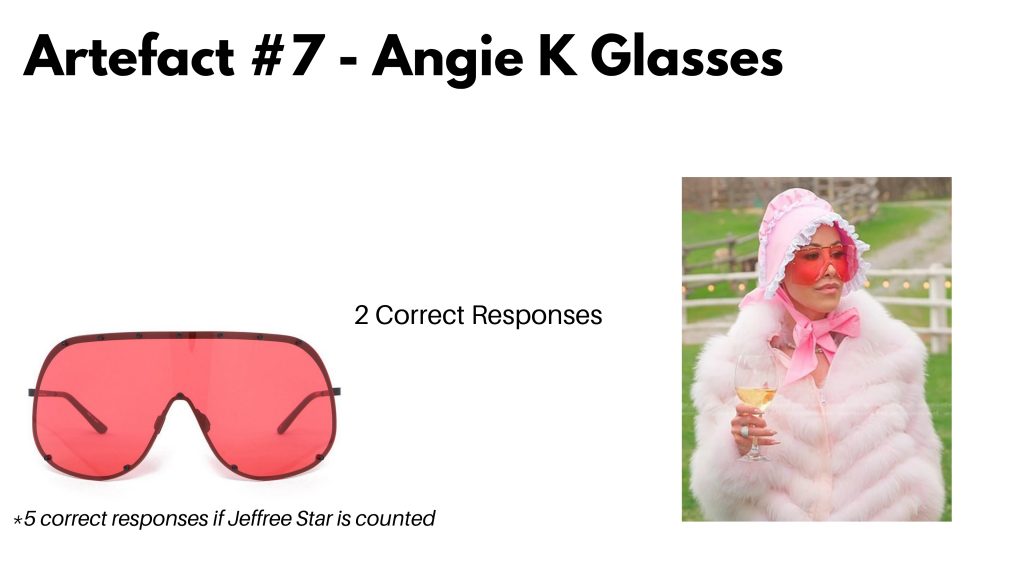

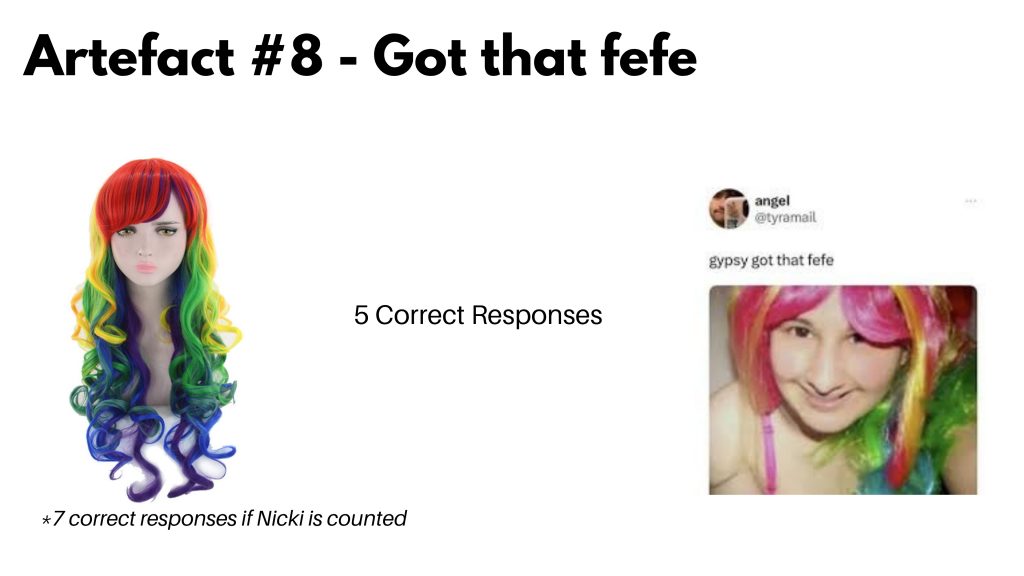

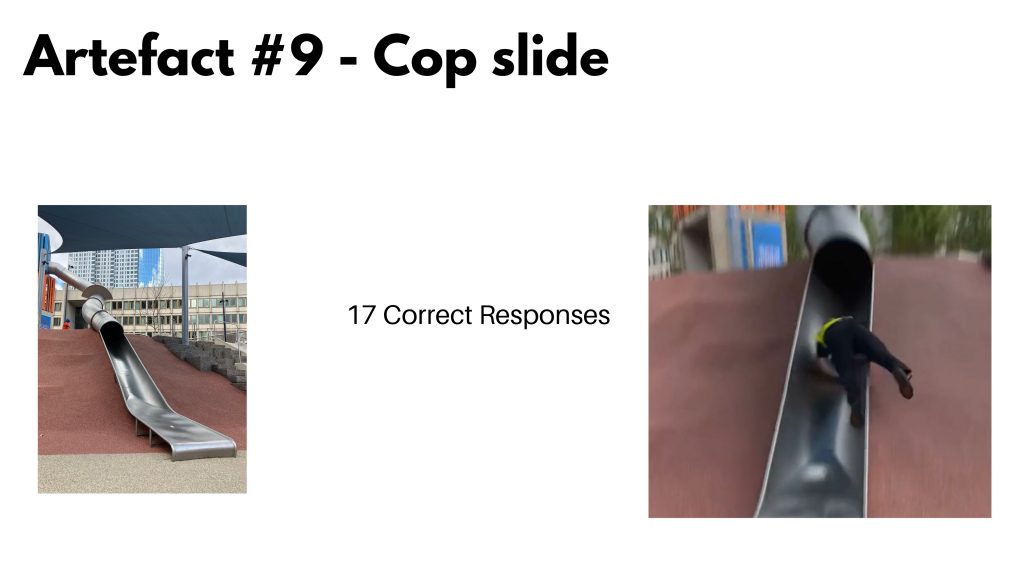

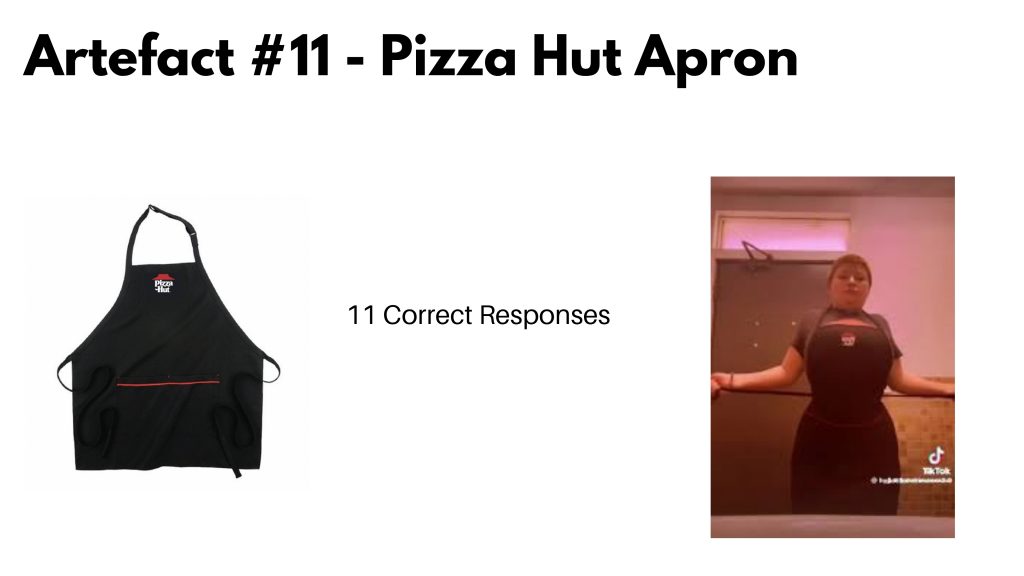

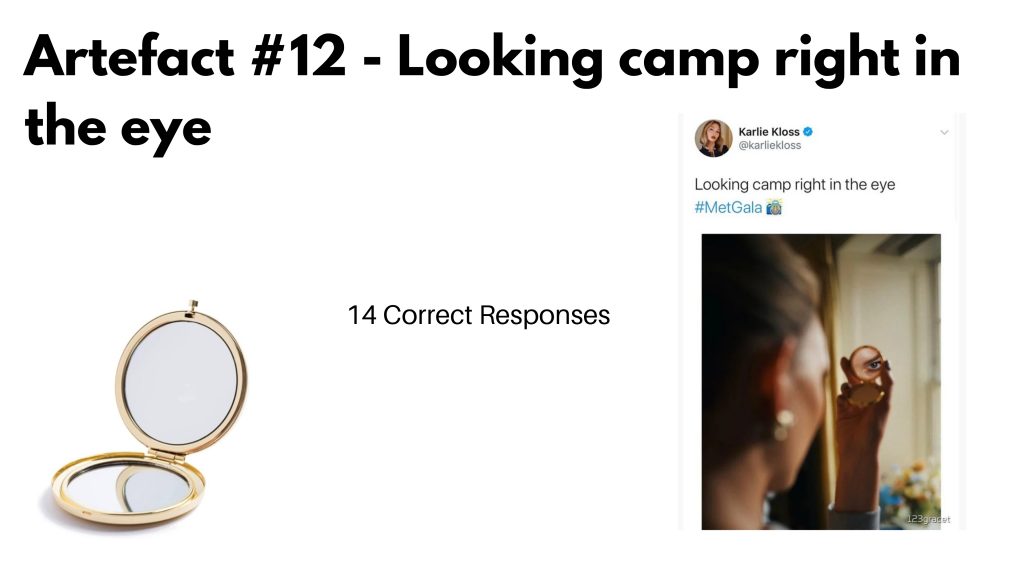

The intervention includes 12 offline artefacts. Check here for the artefacts used.

Below are some findings from the intervention.

Results: 32 participants.

Takeaways:

- Recognition was high, with an average of 9 out of 12 artefacts being correctly identified.

- People who identify as hyper-online or LGBTQIA+ scored higher, suggesting meme literacy aligns with specific online communities (or at least the ones I exist in).

- Younger responders, within the age bracket of 18 to 28 (Gen Z) did better than older age groups.

- “Somewhat online” did not recognise most of the offline artefacts; however, they attempted to be humorous with their responses, incorporating the offline artefact into their own meme.

- Meme recognition is not strictly about recognition but rather cultural fluency.

- Participants who were most active on Twitter and TikTok performed the best; making them the most “fluent”.

- Participants who only use Instagram performed the worst.

- Reddit and Pinterest users tend to give literal descriptive guesses instead of meme interpretations.

Insights:

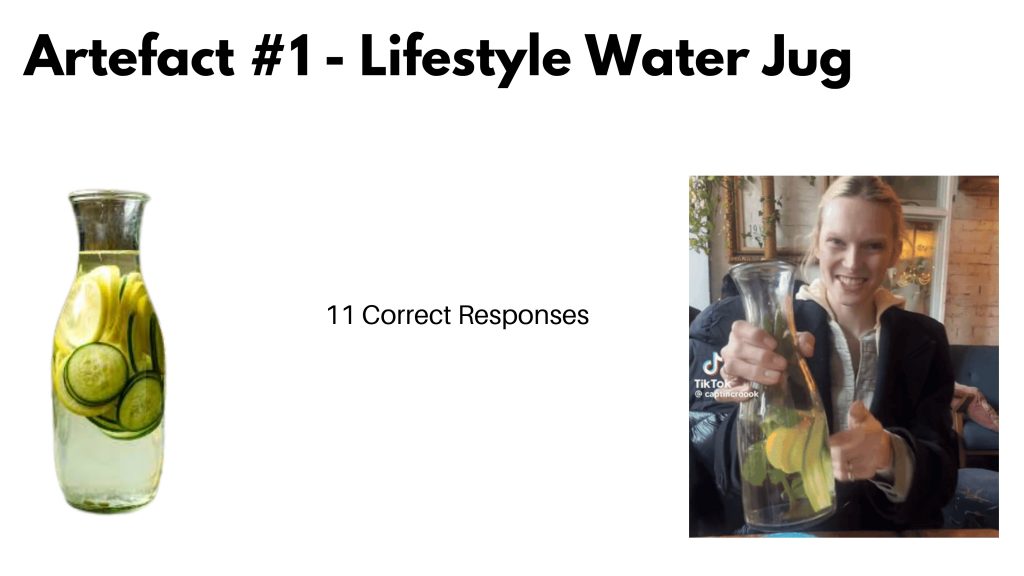

- Some responses to the offline artefacts were technically correct, but phrased through cultural reference rather than the direct descriptive answer. For example, one participant identified the Alex Consani “Lifestyle” artefact with the phrase “miss blaccent in chief yes gawd!” While the words don’t explicitly match, the reference clearly points to the same person in the meme. These kinds of answers were common throughout the intervention, showing how stakeholders who recognised the artefacts often responded not with the literal answer, but in the humorous style of the online community itself.

- The experiment itself became performative, and many participants used the questionnaire to be funny. For example, the participants who said they were “somewhat knowledgeable or “not hyper-online” struggled with the intervention; however still attempted to make jokes and attempt humorous stabs in the dark.

- Several participants found the intervention “humbling,” claiming they could not pinpoint some of the artefacts even with responses such as “i acc thought i would do well at recognising these but now im really struggling” and “I actually don’t know this one ”. This could support the point that few participants saw this as proof of niche meme culture literacy, taking pride in recognising deep cuts.

I’ve decided to also include some quotes taken directly from the Intervention that were interesting and are helping me push my research and process further.

These are some responses to what the participants define as someone being hyper-online:

“I think being hyper online means that I am forming meaningful relationships and having meaningful experiences that centre on my online experiences.”

“I’d define them as someone who spends so much time online that they live in a bubble where, as a community, they create their own online-culture with its own references, vocabulary and so on”

“i think it goes beyond making (niche) references. it’s like when it makes the other person feel like they can’t engage with you because ur constantly spouting random stuff and it makes them uncomfortable”

“Making a online reference offline and hoping the crowd receives it well so you know you’re amongst other chronically online people”

“Constantly scrolling, constantly posting, changing speech patterns according to trendy internet slang / niche meme references”

“Most of your conversational touch-points or things you bond over with others coming from online discourse or cultures”

“idk babe everyones always online even my grandma thats our genrations life so idk what seperates being hyper online”

“Not knowing how to have social interaction offline. Spending more time socialising online than in real life.”

“someone who’s online presence is a fundamental part of their identity”

These are some responses if the participants feel as part of a community online:

“I just want to say I THOUGHT I was knowledgeable in meme culture. After this I think I might not be. Wasted hours online for what?????”

“Its complicated, I think that in part of a broader gay meme culture and sub groups, like (pop music) stan culture and leftist meme communities, but I don’t think these are communities in a regular sense of the word. I’m not “in community” online but my online experiences translate to community with people offline when we get the same references.”

Intervention Link: https://forms.gle/yLE8afmKcTWCt45D8

For the full results of the intervention please refer to the PDF below:

Individual Results: