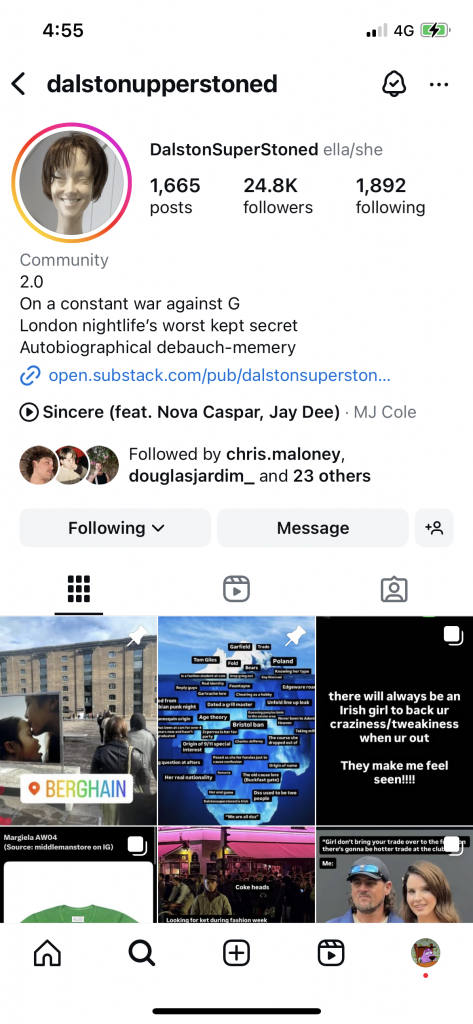

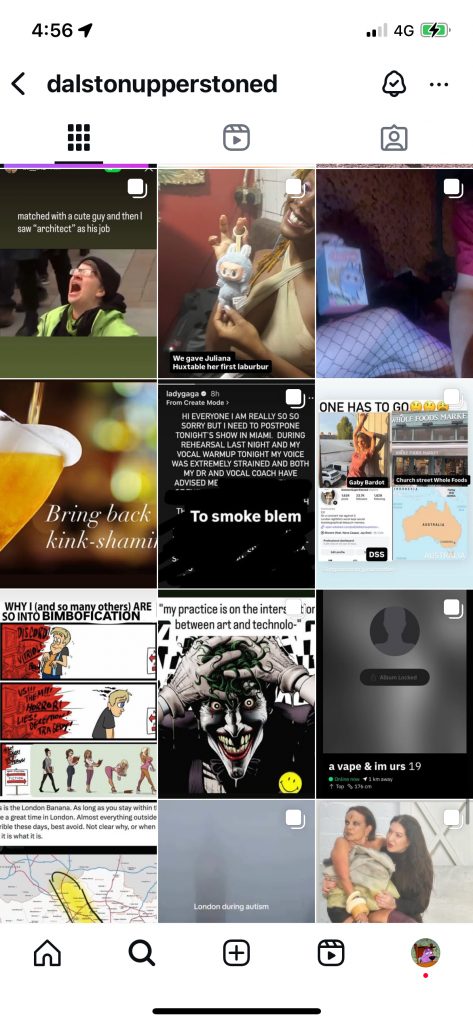

Having the opportunity to meet with Dalston Super Stoned -@dalstonupperstoned (titled after the famous queer nightclub Dalston Super Store) was necessary for me to engage with someone who is deeply embedded in the world of niche memes and hyper-online culture. Known for their irreverent, Gen Z-oriented queer humor and trend awareness, and writing for publications like Dazed makes them not just a meme curator but rather a cultural observer. They were once at 50k followers on Instagram before having their account taken down and starting over.

We began the meeting by going through my recent intervention together. Impressively, they scored 10 out of 13 correct, the highest of any participant so far, which makes sense considering how their account revolved around the same memes that my project explores.

Our discussion moved beyond the intervention and into the broader reflections on meme culture. They explained how their process relies on being in touch with the trend cycle and staying ahead of it, and how it’s unpredictable in knowing what goes viral, as it’s shaped by the algorithm.

“It just ends up happening with how the algorithm feeds it into people”.

When we started delving into the notion of offline artefacts, they recognised its relevance and they proceeded to tell me how they noticed it’s emphasis and visibility within the past two years, especially after the Loewe Tomato Bag. However, they also pointed out that understanding these artefacts requires a level of social awareness and access, saying “you kind of have to be in the know”.

An important topic that came up is their anonymity, which is why this blog will not include any images of Dalston Super Stoned or audio recordings. However, despite remaining anonymous, they mentioned that they are still recognised through their distinct accessories that they post on their account every now and then. People on the streets have supposedly identified them through their headphones that are known to have feathers on them. Effectively make these their own offline artefacts. While they might not refer to a meme, Dalston Super Stoned’ online persona itself could be considered a meme. You can find a collage of all their artefacts in the image below.

When I asked them about examples of offline artefacts, they mentioned how fans of the page would put screenshots of their stories and quotes on t-shirts, and how people dress up as memes on Halloween (including themselves who dressed up as Unfold London sticker for halloween). They even described everyday items like a carabiner as a symbol that has acquired layered cultural meaning within queer communities, making it an offline artefact. Their take on the labubu was quite interesting. I would not have considered it as an online artefact; however, they mentioned “it didn’t start as an artefact, but now that it’s gone beyond the trend cycle, owning one ironically makes it an artefact.”

An interesting point I noted down is how they explained that once they post a meme or a quote on their Instagram story, its lifespan is no longer in their control. It is up to the followers to screenshot it within 24 hours and circulate it. In their words, “once it’s shared, it belongs to the people.” The idea of collective ownership mirrors how memes and the offline artefacts they leave behind live through community participation.

Even though the conversation drifted away from the intervention, it did offer me valuable insight into the validity of my research focus. It showed me that offline artefacts are embedded in the thinking of expert stakeholders. Their reflection on my project also helped expand my understanding of how offline artefacts can manifest, either as fashion, collectibles, or even recognisable personal aesthetics. Defined by the people who engage with them.