To begin testing my question, I wanted my first intervention to be simple and reflective of people’s relationships with memes. What better way to test the waters than by asking people to send me a meme? This was a way to inform my broader inquiry: How can memes as a form of contemporary digital art contribute to cultural experiences and relationships?

Since the target audience of the project is Gen Z, Central Saint Martins felt like the ideal environment to start. Many of the students are largely made up of forward-thinking, creative individuals who often reflect the kind of niche, referential humour that defines the meme culture I’m researching. Being in an art uni like CSM, many of the students engage with visual language in experiential ways, making them fitting participants for my first intervention.

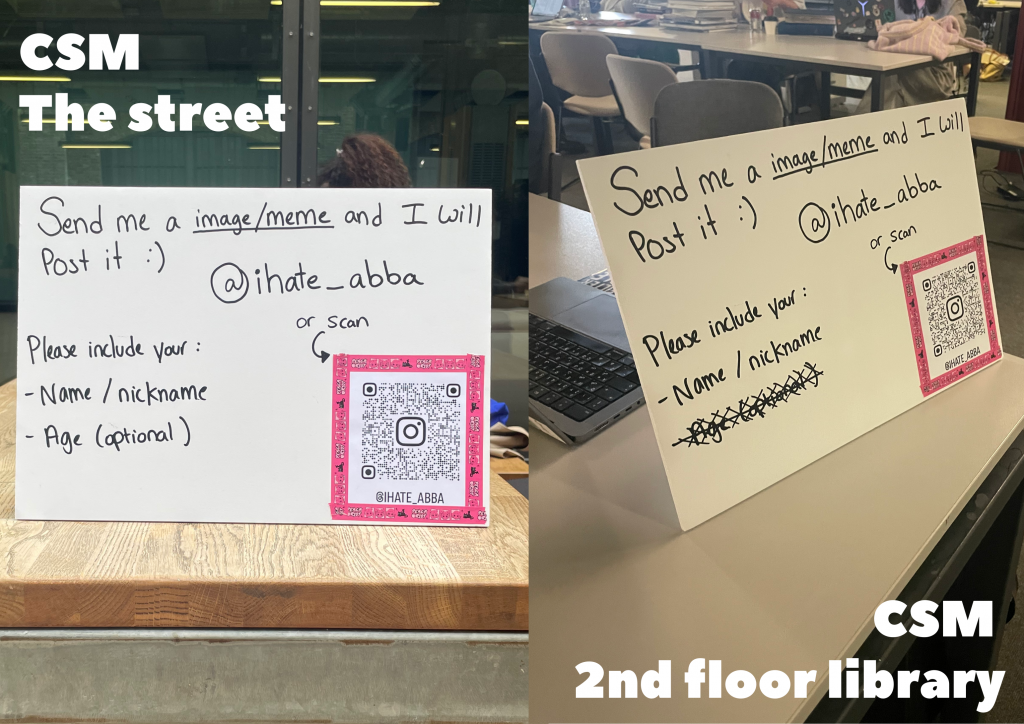

The concept was simple: send me a meme, and I’ll post it. This could be a self-made meme, a candid image with referential humour, or even a well-known meme. Initially, I asked for a meme or image, along with a name or nickname and age. However, after some thought, I removed the age requirement as most students already fell into Gen Z, and I didn’t want to discourage anyone by making the process feel more demanding.

I created a sign with a QR code for the Instagram account to make participation more accessible in case they felt shy about approaching me directly. I also planned on splitting my time between The Street and the library, two high-traffic areas.

After four hours, I received just one submission from Rui, an MA Biodesign student I had briefly met before. This prior interaction might explain why they felt comfortable enough to participate. The meme they sent is screenshotted below.

The purpose of posting the memes on the Instagram account @ihate_abba is to treat it as a kind of open archive or language experiment. A platform where people from different backgrounds and even different languages can connect through shared meme literacy.

While many students stopped to read the sign, none followed through with submitting a meme. This made me reflect on the personal nature of humour and meme culture. For many, sharing a meme offline, especially in a public setting, can feel awkward or impersonal. Memes are usually consumed in the comfort of digital space. As Eli Pariser puts it in The Filter Bubble: What the Internet is Hiding from You, “the internet is a cozy place, populated by our favorite things” (2011, p.12). Attempting to bring this intimacy into an offline environment proved more difficult than expected.

Another relevant observation comes from Gen Z, Explained: The Art of Living in a Digital Age by Roberta Katz et al. They note that “Conversations often spill across offline and online contexts, though some students told us that they found conversation online easier than IRL due to shyness or English not being their first language or for other reasons.” (2021, p.100). This helps explain why students might’ve felt hesitant to engage.

While the intervention was not successful in regards to the number of memes collected, it offered valuable insight into the boundaries between digital expression and real-world interaction. It also made me realise to adopt a more active stance in the next intervention versus the more passive one I decided to adapt.

References:

Katz, R. Ogilvie, S. Shaw, J. Woodhead, L. (2021) Gen Z, Explained: The Art of Living in a Digital Age. Chicago : The University of Chicago Press

Pariser, Eau. (2011) The filter bubble: what the internet is hiding from you. London : Viking